Lilli Lehmann’s How To Sing - New 2025 edition

The following is the preface to the new edition of the book How To Sing by Lilli Lehmann I’ve been working on for the past two years. Make sure to subscribe to my newsletter and follow me on socials to be the first to find out when I publish it.

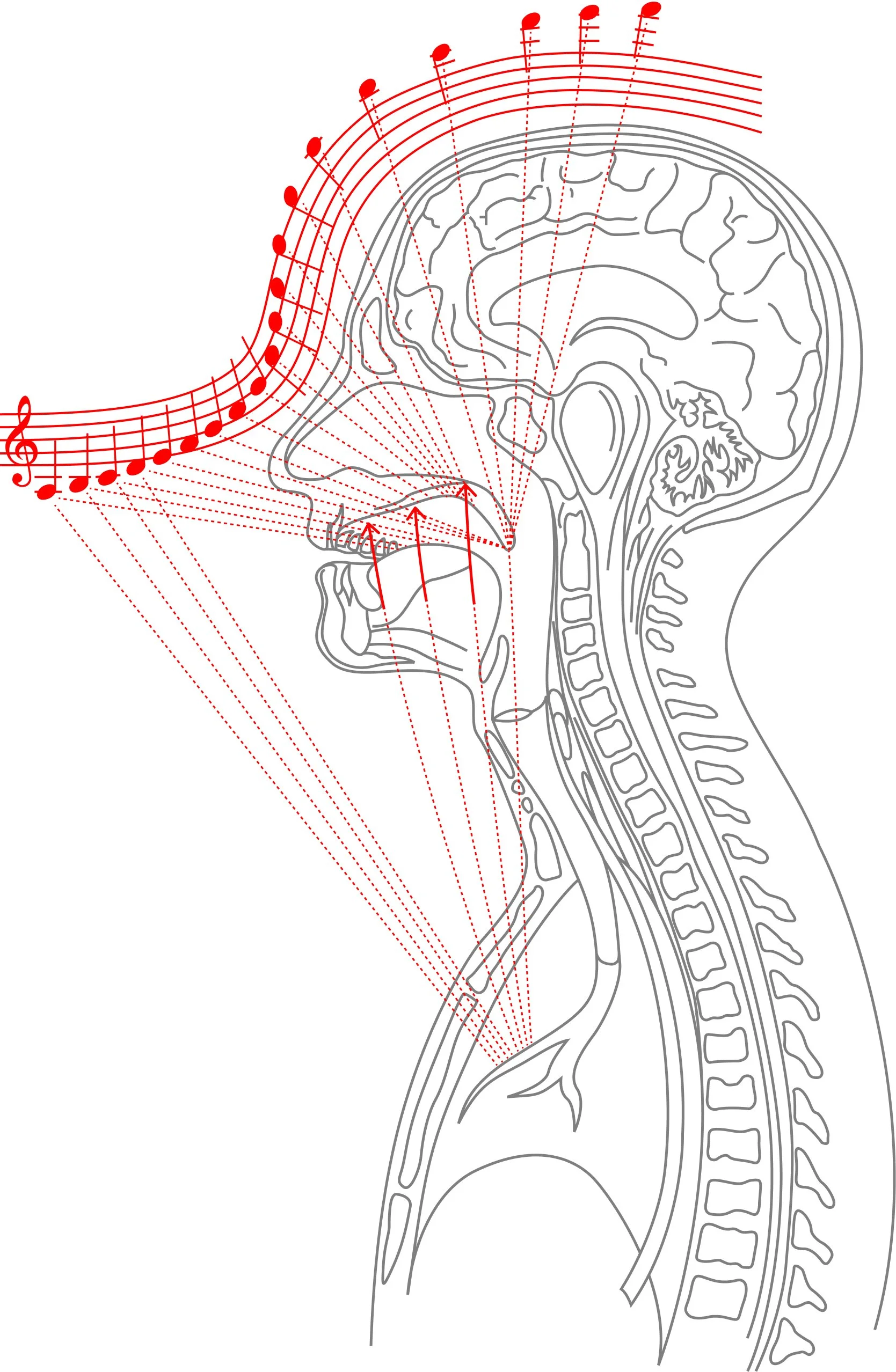

Lilli Lehmann’s illustration on the sensations of the notes for Soprano and Tenor voices. Image redesigned by Alejandro Navarrete

How To Sing has become such a popular book over the decades that I would venture to say that every single professional or aspiring professional of the voice in the West (and an ever increasing number in the East) nowadays, singers and teachers of singing, has either learned from or used some of the material found within these pages or has been indirectly influenced by someone who has. I thought it was quite funny that a book so important such as this one hadn’t been reissued in a way that could be adapted to the needs of today’s students and teachers of the voice.

Art was my all, and only the effort to approach as near as possible to the ideal enjoined me to serve it. ~ Lilli Lehmann (My Path Through Life)[i]

WHO IS THIS BOOK FOR?

How To Sing is a true gift left by a female singer who has been greatly undermined throughout the years; an unquestionable contribution to singing pedagogy, technique, and studies; and the overall result of the work from someone who deeply cared for the art of singing and those who wanted to learn it.

This book was written for classical singers (aka, those who sing opera, oratorio, cantata, lieder, chanson, etc.), but as I have learned over the years, no singer has ever benefited from that which they don’t learn. So, if you happen to be a non-classical singer, I will eagerly recommend you check out this book.

I believe every singer should study classical singing, as classical singers tend to find it easier to migrate to other styles of singing than the other way around. I don’t know if I have ever seen a pop singer sing an opera or a lied (or at least not comfortably), but I’ve seen multiple classical singers sing pop and rock with excellent technique. They’re almost natives in musical theatre in many cases.

But even if you’re not interested in classical music, everything in this book will be applicable to popular styles of music in terms of sensations, physiology, articulation, and work ethic. The technique is a bit different, but a knowledgeable singer (which you will be if you read this book) will know how to identify the differences between the vocal technique he’s being presented to and the vocal technique he needs for the style he’s singing in.

ABOUT LILLI LEHMANN

Elisabeth Maria Lehmann, better known as Lilli Lehmann, was a German soprano, teacher, and author, born in a Jewish family of musicians in Würzburg, Bavaria, on November 24, 1848. London Green described her in Opera Quarterly as “one of the most disciplined and goal-oriented singers of her age.”[ii] She developed such a versatility in her vocal technique that it allowed her to sing from the light coloratura roles of Mozart (like Zerlina, Coloratur Soubrette) to the dramatic roles from Wagner (like Isolde, Hochdramatischer Sopran), from whom she actually premiered and became one of the greatest performers of many of his roles.

She had almost every attribute of technical mastery, and that in a repertory ranging from lieder to folksong, from Handel and Mozart to Meyerbeer and Wagner, from A below the staff to D above. ~ Will Crutchfield

You may have never heard about her, but if you’ve taken at least a few singing lessons, then you’ve definitely been influenced by her work. Although many people before her talked about the sensations in singing, Lilli Lehmann was a pioneer in visual vocal proprioception, that is, she gave us visual ways to feel the relative position of sound in our body and the various muscles and organs utilized in phonation, giving us new ways to apply kinesthesia in our singing practice (feeling the movement of each of these phonatory organs and muscles). If you want to see the pinnacle of her achievements with this book, go check out figure 18 on page 80, because that is the most utilized image in vocal pedagogy up to date, and will probably be used to teach voice students for the rest of history, but we’ll dive more into that topic when you reach that page.

Of course she wasn’t perfect, in her own time she was criticized for her temperament and vocal technique, and her teachings are still debated among professionals of the voice, but for the purposes of this book I will be focusing mainly on the legacy she left us in her work and as a human and an artist.

Perhaps, like many energetic thinkers and artists, she has made her shortcomings the pedestal of her greatness. ~ Eduard Goldbeck on Lilli Lehmann[iii]

At age five, she moved to Prague with her mother and sister and began taking piano lessons at six years old. By age twelve she was acting as accompanist in her mother’s concerts, but her vocal training was an everyday practice, as her mother was an accomplished soprano herself, and took care of teaching her all she knew about the vocal arts.

She made her debut in Prague at seventeen as the First Boy in Mozart’s Die Zauberflöte. Her singing career lasted more than sixty years, and with an unusually extensive repertoire for the times, she is said to have sung 170 roles in 119 operas in German, Italian, and French, all the standard oratorios of her time, and over 600 songs in concert.[iv][1] She is considered a master of the bel canto technique and a prime example of a versatile singer. She sang mainly in Germany, the United States, England, and France, and some of her most successful roles included all three Brünnhildes, Isolde, Venus, Marguerite, Fidelio, Rachel, Donna Anna, Aida, Norma, and Carmen.[v]

Under the pressures of her mum to secure her daughter a stable income, at the age of twenty-one, she signed a life contract with the most prestigious house in Germany, the Berlin Court Opera, in 1870, which she had to break in 1885 to make her debut at the Metropolitan Opera of New York on November 25 as Carmen.[vi]

Lilli Lehmann was very concerned on leaving a legacy, and aside from her singing, which we can still listen to through multiple recordings, she left a great legacy in her writing. With four books, Meine Gesangskunst (My Art of Singing [How To Sing]), Studie zu Fidelio (Study of Fidelio), Studie zu Tristan und Isolde (Study of Tristan and Isolda) and Mein Weg (My Path Through Life), the first about the technique she used for singing, the second and third, published as two books in one, were an analysis to the performance of Beethoven’s only opera and one of Wagner’s most popular musical dramas respectively, and the latter is a memoir, described as a fascinating read that presents an excellent picture of the artistic world of the 19th century and beyond. She also translated and wrote the foreword to French baritone Victor Maurel’s autobiography Zehn Jahre Aus Meinem Künstlerleben: 1887-1897 (Ten Years From My Artistic Life 1887–1897). Additionally, she has become an important figure in studies of vocal technique in books like The Old Italian School of Singing (Daniela Bloem-Hubatka), Singing & Imagination (Thomas Hemsley), Singing: The Mechanism and The Technic (William Vennard), Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy (James Stark), and Singing: The First Art (Dan H. Marek), between many others. The C. F. Peters Corporation even issued two books of sheet music with piano arrangements and German translations by Lilli Lehmann of Mozart arias called Konzert-Arien: für eine Singstimme mit Orchester / W.A. Mozart; Ausgabe für eine Singstimme mit Klavierbegleitung von Lilli Lehmann (or Concert Arias: for a singing voice with orchestra / W.A. Mozart; Edition for a singing voice with piano accompaniment by Lilli Lehmann). While she didn’t regard herself as a composer, she enjoyed writing music and, according to her own claims[vii], one of her works was published by Berlin and New York Publishers, Friedrich Luckhardt and Schirmer respectively, without her consent as her Op. 1, a lied for voice and piano, called Fahr’ Wohl! (farewell), with an English version by E. Buek, for Soprano or Tenor.

She also originated the famous Mozart Festivals in Salzburg (1877–1910), where she worked both as singer and artistic director; to which their immense success was largely due to her efforts.[viii] She had much help in the beginning for every artist was ready to go with her, and she had, best of all, as director Richard Strauss himself.[ix]

She imparted stylistic singing courses at the Mozarteum Conservatory and founded their renowned International Summer Academy in 1916. Lilli Lehmann had a decisive influence on Salzburg's cultural development from 1901 to 1928, where she became one of the city's most important cultural supporters, setting new accents in Mozart interpretation. Her financial commitment to the construction of the Mozarteum building on Schwarzstrasse (1910–1914) and the acquisition of the Mozarthaus earned her the nickname “Mother of the Mozarteum”, the honorary presidency of the International Mozarteum Foundation and, in 1920, the first female honorary citizenship of Salzburg. Since 1916, the Mozarteum Foundation awards the most talented students at the Mozarteum University of Salzburg with the “Lilli Lehmann Medal.”[x]

It was Lilli’s generation that started to perform concerts comprised entirely of Art Songs[2], with no operatic arias in them. According to Sorrell and Potter, “from the turn of the century onwards enterprising singers (Lilli Lehmann, Lillian Nordica, Marcella Sembrich and Ernestine Schumann-Heink in the 1898–9 and 1899–1900 New York seasons, for example) started to offer recitals from which operatic arias were excluded altogether.”[xi] Loges and Turnbridge say, “Lehmann was influential both because of her performance style and because she sometimes gave recitals dedicated to one composer. What is perhaps most remarkable is that her career change is shown to have been as financially lucrative as her stage work (and sometimes more so).”[xii]

Between June 1906 and July 1907, she recorded forty-two records for the Odeon label. According to Will Crutchfield, “Lehmann’s are among the best kind of records to have. They ‘record’ a style whose historical importance interests us, and they can provide aspiring singers and teachers with a really useful standard to strive for.”[xiii]

She's even been a character in historical novels like Painted Veils (James Huneker) and Of Lena Geyer (Marcia Davenport), in which she’s praised as a great singer and teacher of singing.

Her sister Marie Lehmann built a career almost as big as hers but didn’t focus on leaving the legacy that Lilli did in books and recordings. She was a celebrated coloratura soprano in Vienna and often helped and assisted her sister with pedagogical duties and her life on the stage.[xiv]

Her father, Carl August Lehmann, as described by her in My Path Through Life, was a large, strong, handsome, very good-natured, but often very quick-tempered man. He had a glorious voice for the heroic tenor roles. Lilli says she inherited from her father not only his features, but also unfortunately his vehemence. And from her mother, the seriousness and industry. Drinking and gambling, along with other problems, started to take a hold of his life until he was no longer present nor taking care of his family, so Lilli’s mother arranged their separation when her daughter was only four years old.[xv]

Her mother, Marie Löw was not only a dramatic soprano, but a harp player as well. She even accompanied herself in the harp as Desdemona in a production of Rossini’s Otello in the ‘Willow Song’. She was a disciple of Manuel García’s vocal technique[3] and taught Lilli everything she knew about singing based on his technique. At the age of forty-four, she retired from singing to become Professor of the harp and vocal arts in the Prague National Theatre orchestra, which gave her daughters many opportunities to go to the theatre, so Lilli grew up listening to singers schooled in bel canto, and she developed her technical approach based on their models.[xvi]

Lilli Lehmann worked directly with composers and directors such as Richard Wagner, Richard Strauss, Reynaldo Hahn, Giuseppe Verdi, Gustav Mahler, Camille Saint-Saëns, Hans Von Bülow, and Hugo Wolf. Wagner was actually a great friend of the family, Lilli’s mother is quoted by Robert Gutman as ‘an old flame of his Leipzig days’[xvii] and he even tried to adopt Lilly as his daughter when she was fifteen, which never ended up happening because Marie Löw didn’t trust him for a job like that, which was a great choice knowing Wagner’s biography. Lilli Lehmann is credited for popularizing Wolf’s lieder in America alongside Elena Gerhardt, and George Meader. Wagner once invited her not only to sing the First Flower Maiden in Parsifal at Bayreuth, but also to recruit, organize, and train the rest of the cast.[xviii]

Lilli had brown eyes and long, brown hair, which turned white after a certain age. Anna Eugenie Schoen-René describes her as follows, “In later life, Lilli Lehmann gave the impression of being a woman much younger than she actually was. Strikingly beautiful, of a commanding grace, with lovely, classical features, her white hair contrasting with her beautiful, deep, dark eyes, she was always full of animation.”[xix] Musical America described her as “aged, but ageless.”[xx] She never wore any makeup outside of the stage, and lived a pretty simple life, dedicating most of her time to honing her craft and teaching her pupils.

Lilli loved to help any singer who approached her looking for instruction. Herbert F. Peyser wrote the following on a newspaper in 1924, “Lilli Lehmann is the most accessible of people. If you want to see her—you go and see her. You may waive formalities, appointments, letters, introductions, conventional preliminaries of any sort. Ring the front doorbell and announce yourself. Your name and the nature of your business will do later.”[xxi]

She was severe in her criticisms and dominating in her manner of speaking, but this she did because she had high expectations of the people around her, because she herself was someone who had worked arduously on herself and her career and knew what could be achieved through hard work, consistency, and the cultivation of knowledge. While she wasn’t the best teacher, as her patience was short, her directness tended to hurt her pupils’ feelings, and her instructions (as in this book) were hard to follow, she was always open to learn from other singers and musicians about the way they approached their technique and always looked for new ways to teach what she already knew.[xxii] Author Herman Klein summarizes her as follows, “In short, her own standard was perfection; and she demanded no less from all opera singers who professed to work upon similar lines.”[xxiii] Some of her most successful students included singers Olive Fremstad, Geraldine Farrar, Germaine Lubin, Melanie Kurt, Marion Weed and Florence Wickham, although all thought of her classes as an enlightened hell but well worth the agony.[xxiv]

“About this time I first met Madame Lilli Lehmann, to whose far-reaching influence I attribute much of the success which has come to me. I felt the need of the careful instruction of a master. Of course, the idol of music-loving Germany was then, as now, Lilli Lehmann. I wrote to her, asking if I could sing for her with the idea of becoming her pupil.” ~ Geraldine Farrar (The Story Of An American Singer)[xxv]

As for vocal studies, she insisted that every young singer should dedicate at least seven years of their life for voice technique—for voice technique alone.

She never had any children and got married to tenor Paul Kalisch in 1888, at age forty, becoming madame Lilli Lehmann-Kalisch.

By age forty-eight, her diet was almost entirely vegetarian, and she used to have only fruit for lunch. This type of diet is one of the reasons she attributed to her good health and high performance throughout her life.[xxvi] Apart from this, she took morning walks around her home in Grünewald religiously.

Aside from being a singer, director, recording artist, and teacher, she was the founder and financial supporter of a hospital and institution for woman musicians with financial struggles.[4] She was also the founder of protective associations for animals, not only in Germany, but also in France and England. She herself had a dachshund.[xxvii]

As told on an interview by Harriette Brower on the book Great Singers on the Art of Singing, the salon in her home where she received visits was filled with paintings on the wall, a grand piano loaded with music, fine furniture, and a white marble bust as well as a full-length portrait of herself. She did voice consultations for singing students in that very room for a considerable fee that was then donated to her favorite charities.[xxviii] Henry Finck, author of Success in Music and How it is Won quoted that “she intends to leave all her earnings to the Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.”[xxix] And Harper's Bazaar magazine confirmed it as “she is an honorary officer of the Berlin Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, to which organization, according to report, she has bequeathed her fortune.”[xxx] While I have no idea if this was indeed what happened with her estate, all of these things say a lot about the type of human whose work we’re reading.

She died at her home in Grünewald, Berlin, Germany, on May 17, 1929, when she was eighty years old.

The Musical Courier wrote this about her a few days after her passing, “she sang so many different leading roles in so many different operas in divergent styles that it is almost safe to say that she sang “everything.” The lightest roles of comic opera, and the florid roles of vocal grand opera were as welcome to her as the heaviest characters of Wagner. There was never a better Mozart singer, never a better Wagner singer. (…) (Her death) closed the glorious career of one of the greatest women that ever graced the vocal art—a career that extended over a span of sixty-four years and ending only with her death.”[xxxi]

Pauline Viardot described her as “a great musician, a Wagnerian singer par excellence, and a Lieder singer of unsurpassed merit.”[xxxii] Schoen-René wrote that “unquestionably, Lilli Lehmann, in her prime, was one of the greatest sopranos, not only of her own time, but of all time, and her talent covered the entire gamut of song. (…) Her determination and sensitive feeling for the best in art, combined with a wonderful voice, splendid musicianship and excellent health, carried her through to a distinguished career.”[xxxiii]

CHANGES MADE

2024 marked the hundredth anniversary of the publication of the third edition (1924) of Meine Gesangskunst, or How To Sing, as it was published in English, the last edition that Lilli Lehmann worked on and the last with any updates, that is, the 122nd anniversary from the first 1902 edition.

Doing some research, I found out that Richard Aldrich, the translator of the English version of this book, was a music critic for the New York times from 1902 to 1923, which I found pretty peculiar, because for a music critic to take the endeavor of translating a book from the German about singing technique, it must have been a pretty important resource for him, and he must have considered it a very important resource for the public as well, and he wasn’t wrong. With three different editions, multiple reprints, translations to English and French, and the appearances of the most widely used illustrations on the sensations of singing by far, How To Sing has become a must-read for every singer who takes their career seriously.

Reediting this book wasn’t as easy a task as I thought it would be. My main goal was to reissue this book as it was, but with vectorized illustrations, yet as I began to read it and compare it with the original German edition, I found out that the translators for the English version, Richard Aldrich (1902-1914 editions) and Clara Willenbücher (1924 edition), had taken greater freedoms in translating some parts of the text than were really necessary. That, with the addition that this book is from 1902, meant that it was written using old ways of speaking and more embellishments in the way things were written (aka, it had more words than it needed and more than were written in the original German text), and I even found that there were paragraphs that had been completely changed or omitted, presumably with the aim of explaining everything more easily to an English speaking audience, even though the direct German translation would have been perfectly comprehensible. For this reason, I took the freedom as well to adapt some, not all, of these translations to a more modern grammar and redaction and add some of the missing paragraphs (and even chapters!) I found on the original German version that were taken out for the third edition, but about 95% of the book remains intact. It’s pretty flawless, and if there’s any writing problem you find throughout your reading, it was probably me.

For the curious, the chapters I recovered were Section XIV: Development & Equalization; and Section XXI Preparation for Singing. And the chapters that were divided in two for the third edition were: Section XXIII: Connection of Vowels; Section XXVI: Italian & German; Section XXXII: Trill; Section XXXVII: Before The Public.

To write this new edition of the book, I had to compare the digital archives of the texts of the 3 English editions and their multiple reprints from 1902 to 1952, plus the original German text of the first and third editions, because there were significant differences between them at times, as some of them had translation mistakes, odd rephrasing, and even missing pages, as well as examples that were meant primarily to German speakers (mainly on pronunciation). I even kept some of the text that could be found in the first edition but was omitted on the next ones because I considered that it still complemented the text in important ways. I based most of the work on the third edition of the book (1924), but adapted many words, grammars, and phrasings.

I readapted some of the paragraph distributions from the English version to those found on the original German version and even adapted the distributions of a few paragraphs myself. I also kept the chapter distribution of the English version.

Whenever I read a book about singing, I’ve noticed I really appreciate when there are notes on every singer, role, and theater production mentioned, so I added footnotes throughout this book with basic information on each of these mentions, and a bibliography with the sources utilized for my investigation.

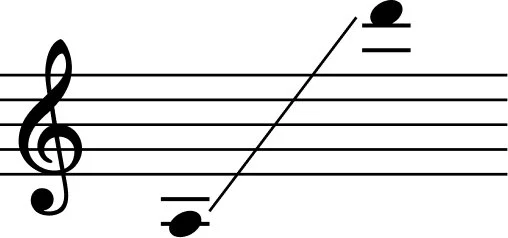

I have vectorized and simplified every single illustration in this book so they can be understood as clearly as possible, without anything that could distract the mind from their main objective. I classified them through numbers 1 to 46. I have also added new illustrations to exemplify parts of the text that I thought could benefit from a graphic explanation. These 25 new illustrations are ordered through letters A to Y.

I have also adapted every vowel and consonant example to the International Phonetic Alphabet’s phonemes (IPA) so that anyone can understand them easily, no matter their nationality, and not get confused by them. So, every ōō, ā, ē, ah, o, ö, ü, oa, ng and y from the original English version are now [u], [e], [i], [a], [o], [œ], [y], [ɔ], [ŋ] and [j] respectively. And if there’s still any confusion, I added an IPA appendix at the end of this book for you to practice your vowel and consonant pronunciation.

As I was reading, I noticed that one of the main differences between the text of the first edition and that of the revised edition of the book was the addition of vowel examples to help the reader understand the sensations of the muscles, the movements of the vocal organs, and the forms needed to project the voice in a healthy manner that were being mentioned. There were also some added paragraphs on the English version explaining vowel formation for English speakers. I decided to not include those added paragraphs, because they confused more than helped, and with the IPA it is way easier to produce the ideal vowels sought in this text.

I believe it’s important to gather knowledge from multiple sources throughout your studies, which is why I added a few comments here and there throughout the book with this gray line on the left to discuss its contents.

* And for short notes, as well as whole added sections, I followed them with an asterisk.

Finally, some of the vocabulary in this book was either pedagogically outdated or unexplained, so I adapted it to the current vocabulary utilized in modern vocal pedagogy—thus, terms like “attack” became “onset” when relevant (but are used interchangeably)—and descriptions for consonants were completely changed to those used in the IPA. I also added a glossary with all the terms that I thought could use a fast explanation as you read, like “breath jerk”, “whirling currents”, or “cantilena”.

HOW TO USE THIS BOOK

Lilli Lehmann didn’t intend to write a physiological work, but simply to attempt to make clear certain infallible vocal sensations of the singer; point out ways to cure evils and show how to gain a correct understanding of that which the student lacks… and everyone’s a student.

Her main worry was that there weren’t many singers who were trained in the workings of their voice. They could sing like gods and goddesses, but whenever they were asked how they did what they did, they weren’t able to explain anything, and that is not real knowledge. That’s an uninformed habit. Something I really came to admire about madame Lehmann as I read her work is that she believes that a true singer is more than a being that produces music through their voice. They are people who worry about helping others be the best that they can be. They are people who train not only their voices, but their mind, body, and brain through the constant study of their craft, their psychology, their gymnastics, and the legacies of the people that came before them.

As you read this masterpiece, you will notice that Lilli mentions the influences and examples of many of her colleagues and predecessors throughout her career. All of these are opportunities for the reader to learn from everything they did right and everything that’s a warning and they should avoid replicating.

The correct way to read this book is from start to end. I wouldn’t recommend anyone to just casually flip through the book, because every chapter is built upon the previous one—unless you’re just looking for the illustrations, which will help you stimulate your imagination at any moment even when you don’t fully understand them. In some chapters it may not appear so, but when you get to the next ones you find that everything was connected all along. Lilli separates the components of singing as well as concepts and problems that may arise throughout the singing studies chapter by chapter, so everything is as clear as possible.

As with any book on singing, you may not agree with everything that’s written in here, but I assure you that this book will significantly change the way you view your body and your singing through the development of your physiological knowledge in relation to the proprioception of your vocal organs and the use of your imagination in your singing practice.

IN DEFENSE OF LEHMANN’S WRITINGS

I wanted to find out what other authors thought about Lilli Lehmann’s writings on vocal technique, and I wasn’t surprised to find mixed opinions about it. (As it always happens in the singing community, because there is no one way of approaching vocal studies.) I will discuss a few of them here so you can have an idea of the type of text you’re facing and how to get the most out of it.

The first thing that called my attention was that Lilli Lehmann was very quoted throughout her lifetime after having published this book, and while there were many other authors who published on the subjects related to the voice, Lilli was most certainly an authority that couldn’t be left behind. When it came to the cares of the voice, the proper ways to study and develop vocal technique, and approach the career as a singer, Lilli was often discussed and invited to share her statements. Richard Faulkner interviewed and quoted her for his book The Tonsils And The Voice In Science, Surgery, Speech And Song as early as 1913. Lilli was considered among the few singers who knew their technique, had long and successful careers, and also learned the technique of teaching singing. Among her contemporaries were Jean De Reszke, and Lillian Nordica.

Daniela Bloem-Hubatka, author of The Old Italian School of Singing, A Theoretical And Practical Guide, complains that what Lehmann presents is not a clear and simple singing method, but a number of her subjective sensations at the time of singing; that the instructions found herein demonstrate the level of absurdity to which the interchange of cause and effect in singing can lead; and that many of its instructions (especially regarding nasal sounds and sensations) are simply incompatible with the Old Italian School of Singing.[xxxiv]

I believe that none of these claims are wrong though, but they come from a place of comparison to a technique that Lehmann didn’t learn. Even Bloem-Hubatka agrees that everything that this book does contain is incredibly detailed (though in a way that makes it complicated to understand), which leads me to conclude that if a singer of the caliber of Lilli Lehmann had such a clarity on everything she felt and did when she was singing, then no singer would be harmed by following her steps and using everything she shares to develop his and her own ideas on the workings of the voice and the sensations of singing.

As a defense to these claims, I would like to quote author James Stark, who writes in Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy that singers of this period were faced with a new problem, which was “having to deal with a wide range of both musical and vocal styles, both the old and new. Whereas previous generations of singers had largely sung the music of their own day, in their own language, singers were now required to seek a technique that would serve equally the several historical styles in which they might sing. The versatility of Lilly Lehmann is a case in point.”[xxxv] This means that the old Italian school of singing was no longer a viable technique for the demands of anything that didn’t resemble old Italian music, this is why Lehmann utilized the teachings of García and her mother in combination to her own experience in singing in different styles and different languages throughout her career to create a technique of her own that was based on the principles of beauty of Bel Canto while still maintaining the expression demanded by dramatic singing and the demands of each language in which she sang.

Author Anna Eugénie Schoen-René in her book America’s Musical Inheritance writes “I must confess that I think her explanations are too hard for any student to understand. (…) Scientific explanations can only be grasped by singers already educated in the principles of their art.”[xxxvi] To this I say that you don’t have to understand everything that you read. The main reason why I read books on singing technique (or any non-fiction book really) is to have a reference for what it is that I want to learn next. Books are allies that you can call upon whenever you need them. There is no need to understand everything at once, but to use what you need at the moment and come back if you need more later. If you are a singer who’s just getting started with his/her studies, I will then advice you to take glances at the content of this book, look at the illustrations, and bring your questions to your voice teacher, because just familiarizing yourself with the contents found in here will give you an edge on your studies compared to everyone else in the world who’s not reading works like this one.

Schoen-René also adds that “here in America, there are many of Lilli Lehmann's loyal pupils, some of them still active in the teaching profession. One of the most loyal, I think, is Geraldine Farrar.”[xxxvii] Farrar was also a great disciple of García, and even though both techniques (Lehmann’s and García’s) had their important differences, she learned to take the best from both of them and use it for her own service. A great singer will never learn from a single teacher, as the only mentor that can really tell them what works is their own body through constant practice, so they have to learn from as many different professionals and students as they can, through lots of practice and trial and error in order to build the technique that serves them the best.

I believe that what makes this book so special is that it comes from a singer who spent a good portion of her career struggling technically, and as a consequence was forced to look mindfully at her technique and approaches to become a true master of her voice and be able to sing in a healthy manner that could be adapted to the demands of the music environment of the time, which wasn’t only the dramatic music of Wagner, that required a voice that could be heard from above a huge orchestra while still remaining expressive and controlled, but also being able to interpret the works of the former composers that the audiences were still clamoring for like Mozart, which required lighter sounds and more fiorituras, and the multiplicity of languages in which they were demanded. They were two different poles of musical interpretation, and Lilli Lehmann learned to master both worlds through a vocal technique that had to differ from the old Italian school of singing, as it had other demands made upon it.

Bloem-Hubatka also says that, “her singing certainly is completely personal in its weird technical devices, all invented by a singer of genius who had to overcome deficient basic knowledge of the laws of vocal production by clever but highly individual manipulation.”[xxxviii]

Author Dan H. Marek in his book, Singing: The First Art says that Lilli Lehmann had an illustrious career by dint of iron determination in spite of a bad method, as she was an advocate of pancostal breathing, for twenty-five years until she became better informed by an Italian colleague. He writes that “thereafter she advised students to seek out an Italian to teach them how to breathe!”. And author William Wennard in his book Singing: The Mechanism and the Technic, concludes from Lilli's poor habits of breathing that, “still it may be said that no matter how well a person sings, if his breathing can be improved his singing can also.” This is why I added a few notes and illustrations throughout the book to help you acquire a sustainable breathing technique for singing (and life in general) that you can still use to apply everything that Lilli teaches.

The only thing I will ask you to not follow from this book is the breathing technique that Lilly utilizes and describes, but I totally recommend you to read it attentively, because it tells you a lot about the workings of the body and what it can accomplish through continuous, conscious practice.

When it was published, the book presented a completely different view of vocal pedagogy that wasn’t based on vocal registers but on vocal sensations, it focused primarily on using physiological knowledge and proprioception to see, feel and imagine everything that goes on at the time of singing, and it introduced concepts like the ‘whirling currents’ to explain the different phenomena of phonation.

I must highlight another thing that I’m simply astounded with about this book. As you will see as you read, Lilli Lehmann made more than 50 illustrations for it, from which at least half of them are explanations of sensations within the body on how it moves and how the voice works in it as you sing. While most of them are exaggerations of the movements to exemplify the sensation and aid the imagination in their application in singing, they are literally ahead of their time, as MRI scans weren’t invented until 1972, 70 years after the publication of the first edition of this book. As I was learning about each illustration, I compared them with real MRI videos of singers I found of the internet, and I was really impressed with the similarity between Lilli’s drawings and real-world examples. Not always, but many more times than I expected, and we will talk about some of these similarities as you read. For this reason, I believe it’s safe to say that this book was ahead of its time and it’s still totally relevant to any singer who wants to pursue a professional career in their craft. It takes the best of both worlds—reality and imagination—for singing, and puts them together into multiple examples for you to use at your will whenever you are practicing, singing professionally, or taking care of your voice on your daily life so that it lasts a lifetime in optimal conditions.

Because this book, nor any book on singing, contains the ones and only fundamental truths of vocal technique, I certainly hope it won’t be the only one on the art of singing that you ever read, as it offers only a portion of the knowledge a singing student must acquire, but it surely is one of the most important ones you can read for you to take your knowledge and understanding a big step further into the excellence you seek to achieve throughout your career.

DISCLAIMER

This book has important differences from the original 1902-1912-1924 version. So I don’t recommend you to use it as historical bibliography for any research you may work on, but I definitely recommend it for comparison and clearer understanding of the text and singing in general.

If there’s anything that you don’t like in this new version of the book, I added my contact information on a final note at the end of the book so you can reach out to me with your feedback and questions, which will be most welcome and taken into consideration for future revisions of the book.

This book will make you think differently about your vocal technique because it will give you practical exercises that you can immediately apply through singing and through feeling your body and engaging your imagination (because some of the most important practices that a singer can have start in the mind… then they can influence the body).

This is the first book on singing that I reedit from an extensive list of books that I would like to work on that are filled with golden nuggets by singers, teachers of singing, historians, and other professionals of the voice and theater arts who left us with lifetimes of knowledge condensed into a few hundred pages for us to acquire in record time and get farther in our careers than they ever did, faster.

I believe that when one of the greatest singers who ever lived writes a book on her technique, studies, and career, it’s unacceptable for any singer walking the path she once walked, with the capacity to read it, to not read it intently.

My hope is that this book will be a great addition to your toolbox of knowledge for your singing studies, the comprehension of the art of singing, and the teaching of all the knowledge you already have and will acquire in an informed manner from a trusted source. I hope this book will inspire you to take its teachings to the classroom so you can discuss its contents with your singing teacher and help you become not only a better singer, but a better human as well, because the world is in need of people who get informed, who ask questions, and who act upon the information they gather to make a difference.

In spite of my age, my experience, and my audacity to reedit a book like this one, I like to think that Mme. Lilli Lehmann would be happy with the final product, and I hope you will be as well.

So, here’s to your success in your career and life as a singer.

Alejandro Navarrete

Santiago, Chile. 2025.

[1] Or 469 Lieder, according to Rosamund Cole on the book German Song Onstage, who researched a handwritten book by Lehmann in which kept record of all her performances, with information of where, when, and what she performed, often with whom, and details on what she wore and important current events.

[2] Art Songs are all the songs intended for the concert repertory, as opposed to a traditional or popular song. These include the German Lieder, the French chanson, and practically any song composed for these purposes on any language.

[3] Manuel García (1805-1906) is a legend in voice studies and the medical world. Inventor of the Laryngoscope, and author of Mémoire Sur La Voix Humaine and Traité Complet De L’Art Du Chant. His school of singing taught pupils like Jenny Lind, Hans Hermann Nissen, Erminia Frezzolini, Julius Stockhausen, Mathilde Marchesi, Charles Bataille and Charles Santley with remarkable results.

[4] While I trust Schoen-René on her words, the Russian website belcanto.ru/lehman.html says, with no bibliography whatsoever, that in an 1896 production of Wagner's Ring of the Nibelungen, Lilli Lehmann donated her entire fee plus an additional 10000 marks to the Bayreuth hospital of St. Augusta to guarantee a permanent bed to poor musicians who needed medical attention. If we take into account the data from the Deutsche Bundesbank (2024) and historicalstatistics.org, this would amount to anywhere from 71000 to 85000 US dollars between 2015 and 2023, plus whatever the amount she earned in the opera production that year.

[i] My Path Through Life by Lilli Lehmann. p.357.

[ii] The Opera Quarterly, Volume 17, Issue 4.

[iii] Die Zukunft, 26. Januar, Bd. 34. p. 178-179.

[iv] Dan H. Marek in Singing: The First Art; and the Musical Courier 1929-05-25: Volume 98, Issue 21, p.35.

[v] The Great Singers: From The Dawn of Opera To Our Own Time by Henry Pleasants. p.234.

[vi] My Path Through Life by Lilli Lehmann.

[vii] German Song Onstage. p. 226.

[viii] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). p.188.

[ix] Schumann-Heink, The Last of The Titans by Mary Lawton. p.180.

[x] Mozarteum University. Personalities Of Salzburg Music History.

[xi] A History of Singing by John Potter & Neil Sorrell. p.197.

[xii] German Song Onstage by Loges, N. & Turnbridge, L. p. 6.

[xiii] Will Crutchfield in Opera News. Vol. 63 Issue 5. p54-59.

[xiv] Toronto Musical Festival Journal, Vol. 1, No. 3, June 1886. p.4.

[xv] My Path Through Life by Lilli Lehmann. My Parents. Whole chapter.

[xvi] Singing In Style by Martha Elliott. p.181.

[xvii] Richard Wagner: The Man, His Mind And His Music by Robert W. Gutman. p.90.

[xviii] Will Crutchfield in Opera News. Vol. 63 Issue 5. p54-59.

[xix] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). (I changed the word handsome for beautiful) p.188.

[xx] R. H. Wollstein in Musical America. 1928-08-11: Vol 48 Issue 17. p.7.

[xxi] The Musician. February, 1924. Article written by Herbert P. Peyser. p.11.

[xxii] The Musician. February, 1924. Article written by Herbert P. Peyser. p.186-192.

[xxiii] Great Women Singers of My Time by Herman Klein. p.223

[xxiv] The Opera Quarterly, Volume 17, Issue 1, Winter 2001, p.10–27. With names added from the Musical Courier 1929-05-25: Volume 98, Issue 21, p.35.

[xxv] Geraldine Farrar: The Story Of An American Singer by herself. p.61.

[xxvi] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). p.186-192.

[xxvii] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). p.186-192.

[xxviii] Great Singers on the Art of Singing by Harriette Brower & James Francis Cooke. p.84.

[xxix] Success in Music and How it is Won by Henry Finck. p.112.

[xxx] Harper's Bazar, 1899-02-18: Vol 32 Iss 7. p.130.

[xxxi] Musical Courier 1929-05-25: Volume 98, Issue 21, p.32.

[xxxii] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). P.186-192.

[xxxiii] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). P.186-192.

[xxxiv] The Old Italian School of Singing by Daniela Bloem-Hubatka.

[xxxv] Bel Canto: A History of Vocal Pedagogy by James Stark.

[xxxvi] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). p.230-236.

[xxxvii] America's Musical Inheritance: Memories and Reminiscences by Anna Eugénie Schoen-René (1941). p.230-236.

[xxxviii] The Old Italian School of Singing by Daniela Bloem-Hubatka.